We are happy to share the last show at 13 vitrine, a project led by our Fellow Stefania Carlotti (Turns #03/#04) and Margaux Dewarrat.

The nights of August 22nd, 23rd and 24th are known in Norway as the “iron nights”. That is when the first

frosts of autumn are expected.

I spend those nights in the woods beside the fire, alternating between feverish excitement, sadness and

tension. The flame dazzles me and I don’t notice it. I listen to the voices of the night while I watch the fire.

The first ones to betray me are my legs. Only then do I think about what I am doing. Why stare at the fire for

so long?

Observing the glow in the dark, I have visions.

Fire is a powerful hypnotic medium, its movements and heat attract my gaze, taking me to a dimension

where time and space are forgotten. I am alone and in the company of everything, my body is no longer

distinct from the environment in which it is immersed.

I thank the sunset, which turned near and dear into far and strange.

The sun of the day came disguised as midnight. Something altered and fierce changed everything.

I can’t tell if the foreboding end of this image causes me fear or admiration, but I suspect both reactions are

pure and proper.

The opaque darkness that has spread over the earth makes my senses vibrate. I fantasize about a new

beginning. Often things appeared upside down, I saw everything with inflamed eyes, a deep melancholy

was master of me. Now it has passed.

The wind echoing through the woods calls my soul back, I feel myself being lifted, torn from my world. I

hear the silent chorus move the flames and weave nature around me.

I give thanks to the night, which lets me admire while it observes everything.

Look

Stare at that blind beast

Only the stars look from above,

Lights, that don’t judge evil

Instead

They feel compassion.

It remains through out the whole day

Under a roar

Of boiling water

From that source is streams downhill

What is down pulls you underneath

It swings,

Swings as if it were held

Because the beast is silent,

But the wind echoes for her

Because the beast dreams

But even if it decided to become such

It decided to close her eyes

and remain in the dream

Forever

We are proud to say that CASTRO Fellows Jacopo Belloni (Turn #05), Caterina De Nicola (turn #01) and Stefania Carlotti (turns #03/#04) are been selected to participate to this show at Centre d’Arte Contemporaine, Gèneve.

From March 24, the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève will present Lemaniana. Reflections on other scenes – a collective exhibition celebrating the diversity of the contemporary artistic production in the Léman region.

Resulting from a call for projects made in autumn 2020, Lemaniana proposes to look at the art produced today in the local area from a new perspective. This project aims to free itself of the artist-invitation protocol, inevitably influenced by codes and value judgements stemming from a single curatorial vision.

The call for projects was therefore based on an open conception of the territory, with the aim of bringing together artists of different background who are either temporarily or permanently linked to the cross-border region of the Lake Léman basin, irrespective of training or education.

The exhibition will thus allow us to navigate through the universe of numerous artists and multiple practices, bringing to light new connections and opening our gaze to fresh interpretations of the world – a world deeply shaken by recent events. Current news – whether we are talking about racism, divergent political powers, gender identity or the pandemic and its confinements – all infuse the exhibition in different ways and give the project a truly contemporary nature, in which everyone will be reflected.

As a whole, what emerges is a new and dynamic art scene, one particularly attuned to the contemporary world. Both intergenerational and international, Lemaniana will be at the intersection of creation and ideas in complete harmony with the most important issues of our time. Works by emerging artists will dialogue with those by their established colleagues, or with the work of unknown individuals who have nevertheless dedicated their lives to their practice. Far from simply reflecting current socio-political and cultural developments, the artists presented here assume and embody change. Their practice, often at the juncture of art and politics, forges the sensibilities of tomorrow.

Lemaniana is a proposal by Andrea Bellini, with the collaboration of Mohamed Almusibli, Jill Gasparina and Stéphanie Moisdon. After examining 829 portfolios, they narrowed the field to 58 artist, duos and collectives, aged between 22 and 87 years old, from 20 nations.

The exhibition will fill all the spaces in the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. It will include the projection of audio-visual works in the Cinema Dynamo, and a programme of performances organized in collaboration with the Arsenic and its director Patrick de Rham, with the aim to be presented in Lausanne during the autumn.

This ambitious project will be accompanied by a richly illustrated exhibition catalogue that will include essays by each of the members of the curatorial committee, as well as a reflection on independent spaces by Roxane Bovet.

With the works of Sonja Aboussouan, Mathilde Agius, Tamara Alegre, Jérôme Baccaglio, Lucas Ballester & Oélia Gouret, James Bantone, Jacopo Belloni, Mabe Bethônico, Yann Stéphane Biscaut, Aurélie Blanchette Dubois, Vivia Braitano, Francesco Cagnin & Lorenza Longhi, Loucia Carlier, Stefania Carlotti, Salomé Chatriot, Adrien Chevalley, Alfredo Coloma, Jeremy Dafflon, Francesco De Bernardi, Caterina De Nicola, Azize Ferizi, Félix Gagliardi, Louisa Gagliardi, Annabelle Galland, Gabriele Garavaglia & Miriam Laura Leonardi, Virginia Garra, Elisa Gleize, Deborah Joyce Holman, Lauren Huret, Inner Light, Luc Joly, Kayije Kagame, Monika Emmanuelle Kazi, Shiva Khosravi, Quentin Lannes, Shuang Li, Hunter Longe, Soraya Lutangu & Ali-Eddine Abdelkhalek, Evariste Maïga, Lucia Martinez Garcia, Lou Masduraud, Lamya Moussa, Johanna Odersky, Valentina Parati, Leonardo Pellicanò, Jessy Razafimandimby, Real Madrid, Anouk Reichenbach, Delphine Reist, Diane Rivoire, Christian Schulz, Rose Siebke Winckler, Terat Thanaworrawatniti, Ambroise Tièche, Remy Ugarte Vallejos, Marco Walpen, Sarah Watson and Mayara Yamada.

ARTISTS TALK:Rebecca Moccia in conversation with Nicola Lagioia

CASTRO hosts a round table discussion with Nicola Lagioia and Rebecca Moccia. The conversation revolves around both their practices with a specific focus on the last Nicola’s book La città dei vivi, set in Rome and source of inspiration for Rebecca’s current work.

Rebecca Moccia (Naples – 1992) lives and works in Milan. After graduating in Sculpture at Brea Academy of Fine Arts (Milan), she graduated in History and Art Criticism at State University of Milan following a research grant at MAC USP, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP (São Paulo,Brazil). From 2012 she is invited to participate in many group and solo exhibitions, among the recent: Chaotic Passion, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce, Genoa (2015), Throwing balls in the air, Franzenfeste, Bressanone (2016); Laboratorio Aperto, XXIV CSAV, Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Como (2018); Il disegno politico Italiano, AplusA Gallery, Venice (2018); Substantial with Ornaghi&Prestinari, The Open Box, Milan (2016); Cuore, Toast Project Space, Florence (2019); Fireworks, Massimodeluca gallery, Venice (2019); Da qui tutto bene, Museo Novecento, Florence (2019); Rest your Eyes, Mazzoleni Gallery, Turin (2019). In 2018 she founded FEA, Festival dos Espaços dos Artistas in Lisbon of which she follows the artistic direction and, since its creation in 2020, she is an activist for AWI – Art Workers Italia.

Nicola Lagioia (Bari – 1973) is an Italian writer and radio host (Pagina3 on Rai Radio 3) and director of the Turin International Book Fair since 2017. Nicola debuted in 2001, with the novel Tre sistemi per sbarazzarsi di Tolstoj (senza risparmiare se stessi) published by minimum fax (Lo Straniero Prize). In 2004 he published for Einaudi the novel Occidente per principianti (Scanno Prize, finalist at Bergamo Prize), and the Napoli Prize.

He has published stories for various anthologies, including Patrie impure (Rizzoli, 2003), La qualità dell’aria (minimum fax, 2004), which he edited together with Christian Raimo, Semi di fico d’India (Nuovadimensione, 2005), Periferie (Laterza, 2006), Deandreide, dedicated to Fabrizio De André (Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, 2006), Ho visto cose (Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, 2008), La storia siamo noi (Neri Pozza, 2008).

With the novel Riportando tutto a casa published by Einaudi in 2009, he won the Vittorini Super Prize, the Volponi Prize, and the Viareggio Prize for fiction. In 2015 he won the Strega Prize with the book La ferocia, published by Einaudi. Until 2017 he directed nickel, the minimum fax’s series of Italian literature. In 2013, 2014 and 2015 he has been a selector for the Venice International Film Festival and in 2020 he was part of the jury of the main competition at the 77th Venice International Film Festival.

ARTISTS TALK: Giulia Mangoni in conversation with Juliana Leandra

She works in Isola del Liri, Italy, and shows with different curatorial projects internationally, recently collaborating with Dreambox Lab in New York, Jacquelyn Strycker in Miami, Prochnik Arquitetura in Rio de Janeiro and CultRise in Rome.

Her work oscillates between painting and performance, and currently investigates the rural, feudal and post-industrial histories and mythologies in the peripheries between Rome and Naples. Representational devices and embodied interventions become a way to metabolize and negotiate these layered influences.

ARTISTS TALK: Pietro Librizzi in conversation with Luca Trevisani

Trevisani has published several books including The effort took ist tools (Argobooks 2008), Luca Trevisani (Silvana Editoriale 2009), The art of Folding for young and old (Cura Books 2012), Water Ikebana (Humboldt Books, 2014), Grand Hotel et des Palmes ( Nero, 2015), Via Roma 398. Palermo, (Humboldt Books, 2018).

ARTISTS TALK: Anouk Chambaz in conversation with Momoko Seto

ARTISTS TALK: Stefania Carlotti in conversation with Gloria de Risi

Gloria de Risi was born in Milan in 1986, where she currently lives and works.

After a BA in Economics for Cultural Heritage at the Luigi Bocconi University in Milan and a MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London, from 2011 to March 2019 she was director of the ZERO… gallery in Milan. Since January 2019 she has been Studio Manager of the artist Cally Spooner.

In 2015 she founded together with Alessio Baldissera and Alberto Zenere Fanta Spazio, a project space dedicated to the promotion of emerging Italian and international artists. After three years of programming from October 2018 the space becomes a commercial gallery, under the name Fanta-MLN. Alternating solo and group exhibitions, the gallery has a particular interest in artists whose practice investigates contemporary art and the systems that regulate it, questioning more or less explicitly their linearity and normativity.

Stefania Carlotti (Carpi, 1994) lives and works in Lausanne. After the Bachelor in Painting and Visual Arts at NABA, in Milan, she pursued an MA degree in Visual Arts – European Art Ensemble – at ECAL, in Lausanne. The most recent exhibitions she participated are Garantie, Wishing Well, Lausanne (CH), curated by Melanie Matranga and Ending Explained, Le DOC, Paris (FR), curated by Will Benedict and Stephanie Moisdon.

Her work is the result of the observation of everyday life from which she takes objects and situations, appropriating them through reproduction, as an attempt to rationalize her place in the world and probably to give meaning to her existence.

ARTISTS TALK: Stefania Carlotti in conversation with Gloria de Risi

Gloria de Risi was born in Milan in 1986, where she currently lives and works.

After a BA in Economics for Cultural Heritage at the Luigi Bocconi University in Milan and a MA in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London, from 2011 to March 2019 she was director of the ZERO… gallery in Milan. Since January 2019 she has been Studio Manager of the artist Cally Spooner.

In 2015 she founded together with Alessio Baldissera and Alberto Zenere Fanta Spazio, a project space dedicated to the promotion of emerging Italian and international artists. After three years of programming from October 2018 the space becomes a commercial gallery, under the name Fanta-MLN. Alternating solo and group exhibitions, the gallery has a particular interest in artists whose practice investigates contemporary art and the systems that regulate it, questioning more or less explicitly their linearity and normativity.

Stefania Carlotti (Carpi, 1994) lives and works in Lausanne. After the Bachelor in Painting and Visual Arts at NABA, in Milan, she pursued an MA degree in Visual Arts – European Art Ensemble – at ECAL, in Lausanne. The most recent exhibitions she participated are Garantie, Wishing Well, Lausanne (CH), curated by Melanie Matranga and Ending Explained, Le DOC, Paris (FR), curated by Will Benedict and Stephanie Moisdon.

Her work is the result of the observation of everyday life from which she takes objects and situations, appropriating them through reproduction, as an attempt to rationalize her place in the world and probably to give meaning to her existence.

LIES LIES LIES by Stefania Carlotti

Floating Slip-Ups & Portable Anecdotes

Giulia Mangoni presents INTERVIEWS FROM LOCKDOWN:

#5

A remote conversation with artist and art-fabricator Eugenio Carabba.

GM: Some of your most recent paintings on cut board have this floating quality to them, almost as if they have emerged from the tapestry of pre-existing marks on the wall of your in-house studio, crystallised for a moment like clouds before disappearing again into the fertile ground of weathered domestic surfaces. There is also a feeling of vast space within these “cutouts” because of your use of colour to create perspective, yet the images dissolve into abstraction as soon as we delve too deep. A sort of balance is achieved, as the objects teeter a few centimetres from the wall, offering themselves up to us as illusionary planes for gazing into.

The work seems so integrated within its surrounding space that I wonder if you are thinking about different readings emerging from its eventual displacement, especially in relation to a more sanitised, traditional art-space with its pristine white walls.

EC: Actually, the shapes at first came by themselves as I was working for a friend in a big project where there were a lot of leftover materials that I ended up partly taking back home. I realised that some of the wood trimmings had something that interested me, something that reminded me of scenography and painted shiftable backgrounds. I reused some of these leftovers for a workshop I did at the Macro, later realizing that something had missed the point : the shapes themselves were the object of attention and the formal investigation didn’t feel resolved. Now I’m taking similar shapes and asking them to act like supports for these imaginary vistas, and it’s pushing me to explore painting for the first time. This is my first venture from sculpture to more two dimensional concerns and I am really aware of how much I don’t know about the preoccupations and history of this medium, let alone the implications of a shift of context in relation to the objects I am creating. What I do know is that I’m much more comfortable painting inside the borders of these shapes than I would be within the constraints of a more traditional squared support.

Even though the surface area seems small for these illusionary images, I am interested in that difficulty, where some things are revealed and others are not. I like the idea that maybe the borders of the image are closing and the viewer is taking some last glances at her surroundings.

In terms of the wall-markings and how they affect my work, my studio is full of these marks, even some drawings done sometime in the 20th century by somebody who added a wallpaper to the room, which I later removed with my flatmate. All of these scratches come from different actions from all these people I didn’t meet, and sometimes I feel the desire to spend an infinite amount of time studying them and their complex morphologies, trying to guess what caused them. Maybe in a parallel life I could have recorded them all and spent my whole life organising them by similitudes, by isomorphic growths, by differences. The fact is they are part of my daily reality and without even knowing it, I absorb them.

GM: In terms of painterly devices and colour choices, the tentative brushstrokes and almost sickly palette creates this atmosphere of a dream revealed, something ominous always lurking, veiled yet in plain sight. The smoke-like wispy quality of the higher and lower edges of these works jolts me away from a comfortable appreciation of what is being depicted into a state of soft vigilance. Something doesn’t feel quite right, the painting is too precariously placed, the edges so thin they are almost blades. Of course, this is only my interpretation. Could you shed some light on your own thought process connecting the supports to the painted scenes?

EC: Actually in a way I think you are right about the sharpness and precarious edges, I never thought about it in this way. The reason I ended up here is that by looking at the leftover scraps from the job I was working on for my friend Leonard, I noticed the quality that this wooden material had to make a clear line when cut; it had the neatness of a precise drawing or the edge of a piece of paper. That’s what interested me at first. I am pairing up the sharp line of the borders of the piece with the out-of-focus painted inside to create a contrast that starts to do something…

The way I see these works is similar to the situation of being in a conversation with someone when everything makes perfect sense and it starts to get a bit boring and you both feel like you have something else to say but can’t quite break the fluidity of sense – and then suddenly you feel an image or a memory or a joke hitting you that needs to be vocalised. There is the incursion of this urgent something that once is out there searches for somewhere to land. When the other person doesn’t receive it or understand it, this thing floats in the air – a gaffe, a blunder.

There’s a part of a book by Adam Philip’s called Attention Seeking (2019) that I’ve been reading recently where he talks about the gaffe as an unreceived and perhaps unwelcome message that has entered the conversation very suddenly, (or maybe I’m confusing myself with Gilles Deleuze’s documentary “from A to Z”). Not that these paintings are jokes, but I am hoping to make them act in a similar way, as disruptive devices that intervene within a room like a gaffe intercedes a tranquil sentence, if that makes sense.

I’ve also been thinking about renaissance palas or orthodox icons in relation to this body of work, for being both serious and funny objects to me. The serious thing is that they have to be portable devices for painting, because canvases hadn’t been invented yet. If calamity hit for example, you had to be able to quickly pack these up and bring them with you, as they were also believed to be of great spiritual importance. Although the function of these objects was quite strict, the idea of these paintings being carried around like portable devices for some kind of other dimension makes me laugh.

GM: They are also like speech bubbles gone wrong, in a very obvious cartoon-like way. It’s almost like you collect all these moments that haven’t hit home, which perhaps explains the feeling of uncomfortableness, of awkwardness, of something too personal or too true and sincere that has emerged when no one wants to hear about it or finds it minimally amusing. These works also feel like solid failed metaphors, like physical anecdotes gone askew. They speak of humour perhaps but maybe a sort of humour lost – the tracings of a story between people that has been launched, looks for someone to receive it but pathetically runs out of steam before it does. I also like this image that if something happens, you have to take all your paintings and run.

EC: HA, Yes exactly

GM: I am curious to know how these sculptural painterly works are coming about, do they start from an original desire or image? Are they planned? Do the paintings and the outer shapes appear together or does one precede the other in the formation of your ideas? What have been the visual and written references surrounding the making of these works?

EC: I prepare the supports before, starting from drawings and then projecting the shapes on the wood. I then stare at them for a lot of time and at some point I just give up and start reading something blandly related or I sketch or I look for things. And then days or weeks go by and one day I feel like I can enter the image, and then without much planning I try to be with the situation I am painting. The moments where I apparently work the hardest are very sparse in comparison to the majority of the time that I spend reading, doing nothing and feeling very frustrated in the studio. Then I realize that those moments of non-work come back into the paintings somehow and are also very important.

For this quarantine and while I work I’ve been reading Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Michel Foucault’s The Care of the Self (1984), Anton Chekhov’s The Steppe (1888), John Ashbery’s Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975) and Natalia Ginsburg’s “The Road to the City”(1949), and “Family Lexicon”(1964). I am especially interested in Ginsburg’s work and am planning to read more of it. I am fascinated by her dry and sharp writing style and the way she approaches her characters, describing individuals, their relationships and how they coexist with both their close social group and the larger power structures during, before and straight after the war. Perhaps, beyond really liking her testimony as a writer, I am finding it poignant that she seems to be describing the beginning of a time that many feel is coming to an end right now.

–

Website: www.eugeniocarabba.com

Eugenio Carabba is also involved in a project of art fabrication that connects and facilitates the work between different industrial and artisanal productive centres of the Lazio region to art/design related projects in Italy. The company is called Fitzcarraldo Fabrications.

The Object-Image

& the Window-Landscape

Giulia Mangoni presents INTERVIEWS FROM LOCKDOWN: #4

A purposefully remote conversation with artist James Hillman.

GM: These new landscapes have emerged in a minimalist, essential language. Some of these works are like train windows or curved airplane windows. There is the idea of something speeding supersonically by – yet a suspended sense of stillness is maintained. The images are visibly also objects; with their rounded top edges. The eye is pulled into the composition at the horizon line, but the unfocused flatness of the surface creates a state of fluctuation, gently pushing the gaze back into the world. I wonder where these works come from and what relation they have with their source material, if they are for you an act of internalising a vast landscape or perhaps the externalisation of an inner feeling, or both.

JH: The paintings came from the immediate landscape outside the studio. They were initially done as a way of engaging more directly with the environment here in rural Italy, where I live, through observation and colour sampling between August to December of last year. The long depth you get with the horizontal field draws you in like you said, but hopefully the fact that they are presented as multiples evidences the spaces between them as much as the visual space created within each one. I am more interested in this area between and around the pieces and in the physical quality of the paintings as objects than in the idea of a series of illusionistic landscapes. I think this is because I’m trying to create the feeling of a much larger field of painting where these are only a few fragments. The more paintings there are, the larger the horizon becomes.

The form of the landscape, using it as an image, a framework from which to work – is useful because it references windows, which are a sort of favourite source-material for me at the moment. I like the fact that when you think of a window it’s an object in itself, but you also use it to see outside. It may sound obvious but sometimes you forget this, and I work to try and point out the material qualities of the object before you can ‘see through it’. This is why the edges are curved, to disturb the illusionary plane and to create a back and forth between the two readings.

GM: Are these finished?

JH: The images themselves are finished as individual parts; the display mechanism not yet.

I need to understand how to hang them, in terms of the separation from each other in order to potentialise their in-between spaces. I’m thinking a lot about Judd and Irwin, the relationship between the art object and its environment. I’m asking myself if whether to appreciate the work it’s better to activate the environment, rigorously controlling it, or if a painting can be introduced that changes the environment simply by being in it.

GM: This is the first time I see you working in fragments, expanding this modular way of making into the curation of your work. You are creating an environment without having to physically modify the whole environment, unlike what you did for the Soft Furnishing installatory exhibition in São Paulo (2019). There you showed these meticulous gradient paintings with tiles to match them on the floor and wallpaper made especially for the pieces lining the gallery. Interestingly, it became really difficult to remove those objects once they had been contextualized in that setting. The problem was you were still trying to present them as individual pieces afterwards, and they had acquired a sort of ‘aura’ whilst being in that space. The other opposite would be your rain-room installation Spring / Horizon for the CultRise Aurore group show in Rome (2017), a whole experiential environment without a single loose item. I’m wondering if you often think about where the work is going to be shown when you make it and how much of that kind of thinking has shaped these investigations of single object VS installation in the last three years.

JH: I find this a very interesting dilemma. On the one hand I get great joy from full blown experiential installations, but the necessity of heavy installation work tied to a single place, more likely than not towards an extremely short lived moment, bothers me. There is a reduction in accessibility in the sense that the redisplay of these works is very rare, and in general, they rely too much on the superstructures of galleries, museums and a high rank of specialised collectors. It is an over said thing, but we live very wastefully and the minimalist doctrine has a large draw on me for this reason. Irwin changed an entire room with a single piece of black tape. I would really like to be able to create individual paintings that can exude that sort of influence over a multitude of distinctly different spaces, from the gallery to domestic settings. And that the effect they have, whatever it is, multiplies drastically when they are brought into close contact with each other. Ha! It’s a big ask.

GM: These small framed landscapes sit quite comfortably within their frame, each one exuding its own subtle message yet content in its group setting. In the row to the right, the rectangular images seem to want to wiggle away, there is something humorous, flag-like, sensual about them, maybe in relation to the more sober left column. Modifying their form shifts the narrative of the work, these wavy pieces seem much more energetic and sculptural than their rectangular counterparts. I wanted to know more about how these works responded to each other and how you are thinking about the integration of sculpture and painting in your practice.

JH: These all emerged as the original studies of the larger Landskip series. The more rectangular pieces are read as horizon lines and let your eye recede into the picture plane. The ones on the right were treated as if the light and darker tones were high and low points on a piece of sculpture, as if light was falling across a curved form, which is accentuated by cutting the paper. The relation you have with the work becomes much closer and it becomes more immediate within your realm of palpability. Again, it’s that play of trying to evidence the object whilst also providing the illusion of a deep landscape. I am increasingly looking for these multiple depths working together on a single plane.

I am also thinking about digital screens here and how the images that they display seem to have a certain fluid quality to them. Even if materially we know the screen is solid, the image on the screen of a plasma television seems to lose all sense of ‘objectness’. I think painting holds the solidity of the image much more, and the cut-out forms of the support of these works forces you to relate to them both as images and also as objects in the room. The image then becomes inextricably linked to the painting’s own sculptural form. I think overall I’m trying to see what happens when illusionary images also function as projections of their underlying structures, and exploring ways to make apparent their material-object origins.

–

James Hillman in represented by Lamb Arts and is currently showing a piece through the Royal Scottish Academy annual exhibition now online due to COVID-19.

Website: www.hilmmanjames.co.uk

IG: jmshillman

Maximalism, Modularity

& Seemingly Futile Laborious Processes

Giulia Mangoni presents INTERVIEWS FROM LOCKDOWN: #3

A remote conversation with artist and curator Jacquelyn Strycker

GM: Pattern-making and your interest in kitsch is palpable in your recent Patchwork series, which is a beautiful body of work, yet in pieces such as Quilted Medley, something disrupts the harmony. It’s as if these works refuse to recede completely into the role of being decorative objects for a wall in a domestic setting. You move between quilted paper landscapes and more minimal, subtle interventions through works like Folded Grids. This oscillation reinforces my reading of your pieces as meditations between dualities, elegance and vulgarity, ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, as well as notions of women’s work in relation to the history of abstraction in a capitalist system of commodification. Can you talk us through the processes behind these different two-dimensional works?

JS: The Patchwork series is about maximalism–thinking about excess, taking the decorative and pushing the limits of it in each piece. I use a lot of 70’s fabric patterns and look at a lot of vintage quilting magazines for inspiration and the specific ways that those patterns come together. When I’m layering all these patterns from different sources on top of each other, I kind of imagine working like a confined housewife who is just “going for it”. She has no sense of an “appropriate” place to stop and does not care about what the pattern-book says. She does not exercise any restraint. What results is an image where all these different patterns kind of throw up on each other. It is both beautiful and vulgar, they are a little ‘too much’ at times, not giving your eyes a place to rest. They are meant to be overwhelming in that way.

GM: This is exactly what I meant with the word vulgar, as the opposite of taste when taste is something that lets you rest, lets your eyes recede into the picture plane, and brings calm into your home. You create something that is alluring and feels like one whole image but then it disrupts your gaze into fragments, causing an irritation that sparks thought.

JS: The play with taste is very important. The Folded Grids series, on the other hand, is an exercise in restraint, but also very much related to the Patchwork series in the idea of a futile or unnecessary labor involving outdated technologies. With Folded Grids, I used the Risograph machine to print onto fabric, which you are not really supposed to do. I had paper-backed fabric that I ran one sheet at a time – a totally inefficient way of using this already dated technology.

In fact, I started off by hand drawing and painting these grids, scanning them in, doing the colour separation on photoshop, then printing them through the risograph onto the fabric-backed paper. Once I was at this stage, I put these back into the scanner and fold them into different shapes, THEN I did new colour separations and printed them out again. Some of these were mismatches from two separate versions and the folds don’t really align on purpose.

Long story short: it’s about absurdity, even though that might not be entirely visible when you see them online. There’s just a ridiculous amount of work involved in making the final product, similar to a lot of crafting at home these days, whether that’s knitting a sweater, or making your own cheese. But that unnecessary labour attaches itself to the object in some way. When you look at them there’s a confusion about what it is you are looking at–paper, fabric, or a digitalized rendition of both. And there’s a sort of humour for me regarding the amount of work taken to make this simple, little, restrained, folded modernist grid. I’m still working out how I want to show them best and trying to figure out how I can bring in the story of their process curatorially, perhaps even including the original printed fabric .

“The project, developed while a Gaia Studio Wonder Women resident, and realized at Gallery Aferro, brings together food and music. Elements include photographic wallpaper of homemade tapes, digitally printed domestic textiles such as a tablecloth and tea towels, an artistbook/ zine with recipes and lyrics, artwork made from cassette tapes, an editioned mix tape with a suggested song and snack pairing insert, and a mix tape making station”.

GM: In projects like ‘DRINK WITH ME’, ‘MIXT TAPES | MIX TAPES’, ‘ZAZAZA’, your aesthetic practice spills and mixes with more social and relational events. By adopting processes of industrial printing on materials that can be reintroduced into the rituals of commonality, you seem to dissolve the ‘art’ from the ‘object’, expanding a set of layered aesthetic relationships to a whole event and its participants. I was wondering how you transitioned from individual studio-based work to work that verges on social practice, and how you deal with the shifting value systems between both?

JS: I think the works are all related. The work on paper is looking at patterns referencing the domestic and excess and this sort of celebratory excess of domesticity, instead of hiding it – and that’s also what is happening with the more community oriented relational projects. And in both there is always a play with the structures of labour.

So with Drink With Me, I used flat origami patterns to make a cup, the idea was that I didn’t fold them for people, if you wanted a drink of water or wine, you had to fold your own cup from the pack. The whole event revolved around the act of folding one’s own cup, which pointed again at this idea of absurd labour. The cups were also a bit too small and quite awkward to hold, and the fact that people had to figure out how to make their cup didn’t add to the functionality of these objects as temporary liquid holders.

The first time they were shown, I had a GIF showing the cup being folded as an instruction that played on a loop. Later there was concern that the video or GIF wouldn’t be enough for people to follow the steps correctly, even though the whole challenge and frustration and eventual spread of the ‘successful’ way of folding these cups was entirely the point of the whole experience.

In any case, the second time I showed them, I stood for the entire opening folding and unfolding the same cup. Some people of course still didn’t get it and created their own cone mechanism and had to drink as fast as possible to try and not get wine or water on their clothes. So as a piece, it’s meant to be frustrating and funny and to bring people together.

“PROGI is BINGO night meets pierogi dinner in the form of a participatory art event. Participants are served a meal of homemade pierogi, applesauce, sauerkraut, kielbasa, bread and sour cream. As they eat this meal, they play a customized, BINGO-like game, PROGI, in which the playing cards have been customized with drawings, prints and images from local artists. The first PROGI took place in June 2013, in the basement of the Polish National Catholic Church of the Resurrection, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn”.

Text and Images courtesy of artist’s website

GM: Your project ‘PROGI’ seems to be the culmination of all we’ve been talking about.

JS: It was actually the first relational project to come about, when I was living above the rectory of a Polish church in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I grew up eating and making pierogi. In America, at least, there’s this tradition of churches hosting BINGO games in their basements, and I got it in my head that I wanted to have a Bingo game meets pierogi dinner in the basement of the Polish church. So I made these Bingo cards that had ‘progi’ written on them instead of ‘bingo’.

With the quilted works on paper there’s something systematic–geometrical, mathematical, like a set of indecipherable hieroglyphs collected and displayed. With the Progi Bingo project this was also the case – generating the numbers for the grids was both systematic and disruptive. I ended up giving a bunch of these cards to different artists who I knew so they could alter them as they wanted, through drawing, printing, painting and collage, returning these cards for the actual bingo game. In the event, each person at the table had bingo blotters, (fat markers pens), which meant people were drawing on top of the drawings, turning the original pieces into a cumulative, collaborative thing.

In the meantime I was cooking in the basement and struggling because the pierogi was all falling apart. A friend of mine had to come to my rescue! Her family owned a Chinese restaurant and she taught me how to make them the way you do dumplings. So an amazing turn of events saved the day. This friend also acted as the bingo caller, calling out the prizes, and overall it became a really fun, unscripted event–different and better than what I could have imagined.

GM: Going back 180° to your two-dimensional work, I am very interested in your new modular experiments, where you have been mounting paper on board and creating cut-outs with flaps that open up like advent-calendars. They seem to offer themselves up to touch, use and re-arrangement, and I wonder if you have been influenced by your daughter Poppy and the relationship children have with craft and with playing.

JS: Actually, I’ve been thinking a lot about this: Poppy is always making these assemblages with anything she can find, even using a projector that we have for the TV connected to the Internet. She knows how to turn it on and move it and point it towards different angles, and in this sense she seems more technologically advanced than me in my investigations! But it’s definitely influenced what I’m doing. I’ve been thinking a lot about building blocks and tangrams, those specific sets of shapes that you can move to make other shapes, dominoes and matching cards, things that you can keep shuffling around. There is an element of play there that is influenced by kid crafts and kid games.

The modularity of this work has been important for me. Raising a child in a small Brooklyn apartment, and not having an external studio for a while, I had to make work that I could mount and dismount, that I could tile together to make something larger, and then pack up and put away in a box. Now I have a studio because Poppy’s in Pre-K, which helps a lot – but at this very moment where we are all at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I am back home and in the world of modularity.

I was definitely thinking about advent calendars with the new works on paper, and I’ve been toying with the idea of putting something edible inside these too. Or those origami “cootie catchers” that you make as a kid. Maybe I need to make some really crazy ridiculously ornate cootie catcher work to combat the corona madness.

–

Website: www.thestrycker.com

IG: thestrycker

Gender, Domesticity & the Idealised Wildness of Nature

Giulia Mangoni presents INTERVIEWS FROM LOCKDOWN: #2

A remote conversation with artist Sarah G. Sharp,

through the lens of an intersected historiography.

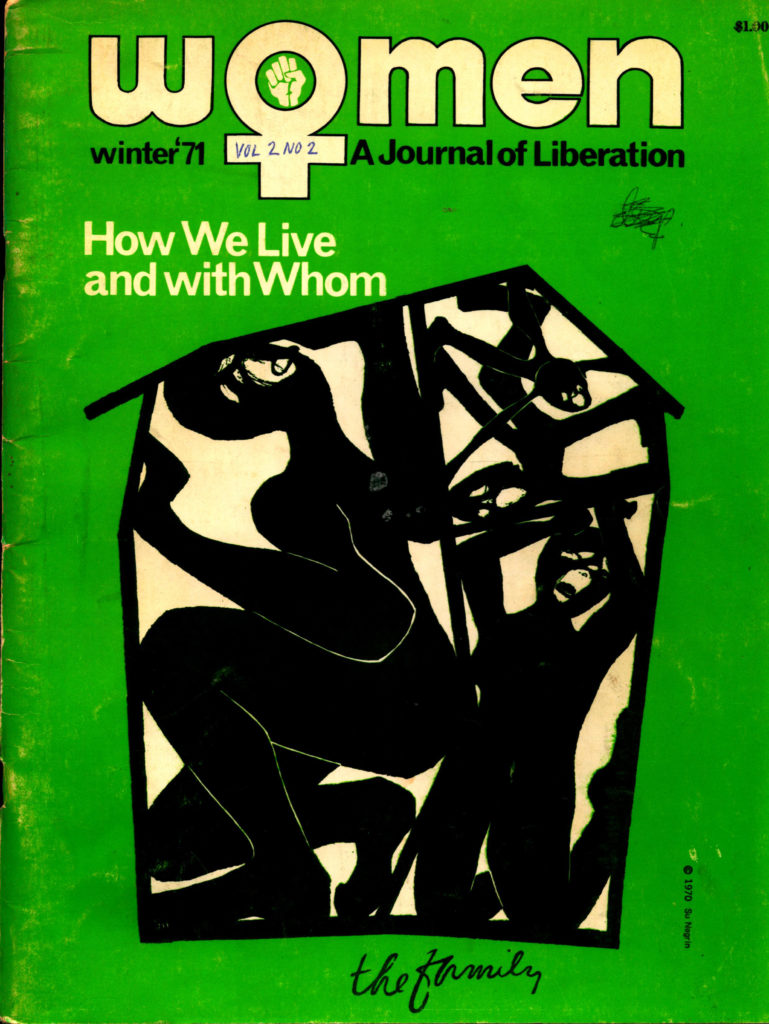

“These collages utilize found images of communes and idealized nature on the west coast of the US from popular media sources like Time Magazine. Most of these images are from the late 1960’s-1970’s and represent popular media’s attempt to explain utopian subcultures to American society at large”.

Images and text courtesy of artist’s website

GM: In your research-based work ‘The Youth Communes and the Pacific States’, you process the media’s attempts at making ‘digestible’ the idea of a commune at the fringe of society to the general American public in the 1960-70s. Can you talk us through what happens between the source material in the form of printed documentation and your own manipulation of this historiographic trace in the present?

SGS: I was interested in this movement in time where people launched out into the land to build their own communities as antidotes to the problems of modernity, rejecting the conservative American narrative whilst also basing themselves on prescribed divisions between urban man and the idealized wild nature beyond the cities. I started working with LIFE magazines from the 1960’s and early 1970’s, which introduced these revolutionary ideas into the normative American home. I was especially interested in opening and disrupting the original documentation of these movements so as to make evident the complications and interconnections between utopian ideas and their re-insertion into mainstream culture.

Through the hand-embroidered diagrams and threaded interventions I wanted to remove, obscure or draw attention to certain incongruencies of class and gender that seeped through in these images of the struggle for Utopia; especially ideas of “naturalness” reinforcing gender roles.

Autobiographically speaking, my dad was part of the counterculture and lived on a commune in the 1960’s, but then became a fundamentalist Christian. I was actually brought up in his fundamentalist Christian church in the 80’s. I am part of a generation, especially growing up on the west coast of the US, whose parents created and participated in these countercultural practices and spaces. So, I was also thinking about the gap between his lived experience and my understanding of his history and the counterculture. Media narratives kind of “filled in” those gaps for me during a childhood that was super-saturated with christianity and a lot of fear around non-traditional ways of living. My work draws on a kind of re-interpretation of the religious iconography and the geometric patterns that could be both DIY instruction manuals for self-sustained living and mystical annotations.

“In 1975 NASA sent two rovers (Viking I and II) to Mars to survey the planet’s surface. During the same year a group of women in the Pacific Northwest formed what became known as the Oregon’s Women’s Land Trust. Land purchased by the OWL Trust became the site of separatist wimmin’s land where women from varied backgrounds developed new modes of self-sufficient, rural, communal living. Finding Our Place in Space complicates these historic, gendered, technophobic and technophiliac narratives by combining documentary notes, text and images from these momentous events”.

Images and text courtesy of artist’s website

GM: I am revisiting your project ‘Whole Earth Systems’ with accompanying publication ‘Understanding Whole Systems’ (2016), and video piece ‘Finding our Place in Space’(2017) )[1]

The two separate yet parallel events that appear in these works are strangely connected to each other. By overlaying craft-oriented geometrical patterns over fragmented documentation of both events, a wobble is caused in their parallel historic narratives as we cognise them in the present. Could these disruptive methodologies be said to set the terms or draw upon a kind of ‘feminist historiography’?

SGS: Finding a Place in Space combines text from the founding of the Oregon Women’s Land at Owl Creek in 1975 with media from NASA’s launch of the Viking I and II Mars Landers during the same year. The Viking Landers photographed the surface of Mars for the first time, as part of the “search for life” in space. I was interested in how these extraordinary efforts that seemed to belong to all mankind, and these smaller collective actions emerged from the same place; a recognition that human interaction with the Earth, and western society as it stood, would eventually become unsustainable. Humans were beginning to realize they might need another plan, and I wanted to explore these two extreme branches by placing them alongside each other. Would the future of mankind be best served by space travel and living on Mars or the abandonment of cities and moving to self-run alternative communities? These were answers at two different scales and born out of different sets of priorities, but with common underlying contexts. I was especially interested in the value and importance of land itself in these two solutions, both in space and on earth, in light of American foundational history and the associations between land and power. For NASA, colonization of another planet, and therefore new land to live on, was a distant hopeful goal. For the women of OWL, land ownership represented a kind of potential sovereignty and new self-governed social structure.

Reading the actual minutes of the founding of the Women’s Land in the video and using open source images made by women of the Land Trust were really important for that video piece, letting the narrative that was already there come through and reframe these other narratives produced by Nasa.

I think there is feminist historiography, which started to be broadly framed and recorded in the 70s, in regards to reworking history, and then gained a space in academia and other kinds of publishing. But, I am most interested in not putting “a circle” around a specific kind of historiography or method of collecting and passing on history so as not to remove it from other historical narratives. It is pivotal instead to re-attach them, to cognize the different histories and to situate them in relation to larger narratives. It is, of course, important that communities produce their own historiography and for these narratives to be centered on people’s experiences, but I am most interested in how these histories overlap, bleed into each other and are invariably intersected with each other.

[1] For full 11 minutes of ‘Finding our Place in Space’, click here.

“The Tool Book Project is a semi-annual publication that showcases art, writing, dialogue and critical discourse from an international group of artists and cultural producers. Tool Book is also a platform for sharing resources via curated gallery shows, readings, roundtable discussions, andother public events. Sales from the publication are donated to specific social and environmental justice organisations, providing a mode of direct action for artists and writers to exchange ideas and affect positive social change”. [1]

Images and text courtesy of artist’s website

GM: I wanted to ask how you transited from more individual research-based projects to more socially oriented projects like ‘The Tool Book Project’, and if you see the creation of this publication as a community-building platform?

SGS: I had been thinking about how underground, activist and other non-mainstream communities connected with each other prior to this huge digitalisation of communication. As I was conducting research in various archives of underground newspapers and radical literature, I thought about how these communities that were linked to small-scale publications sent through the mail were less rhizomatic in growth and you could trace how they grew. These publications represented a smaller, perhaps more civil example of what media scholars might call “the many speaking to the many’, as opposed to the “few speaking to the many” in mass media. Now we live in a media culture where “the many speak to the many” in a way that can be overwhelming; where there is no editorial voice, for better or worse, and we have bots and trolls that interfere in our localised and communal discussions from decontextualised places.

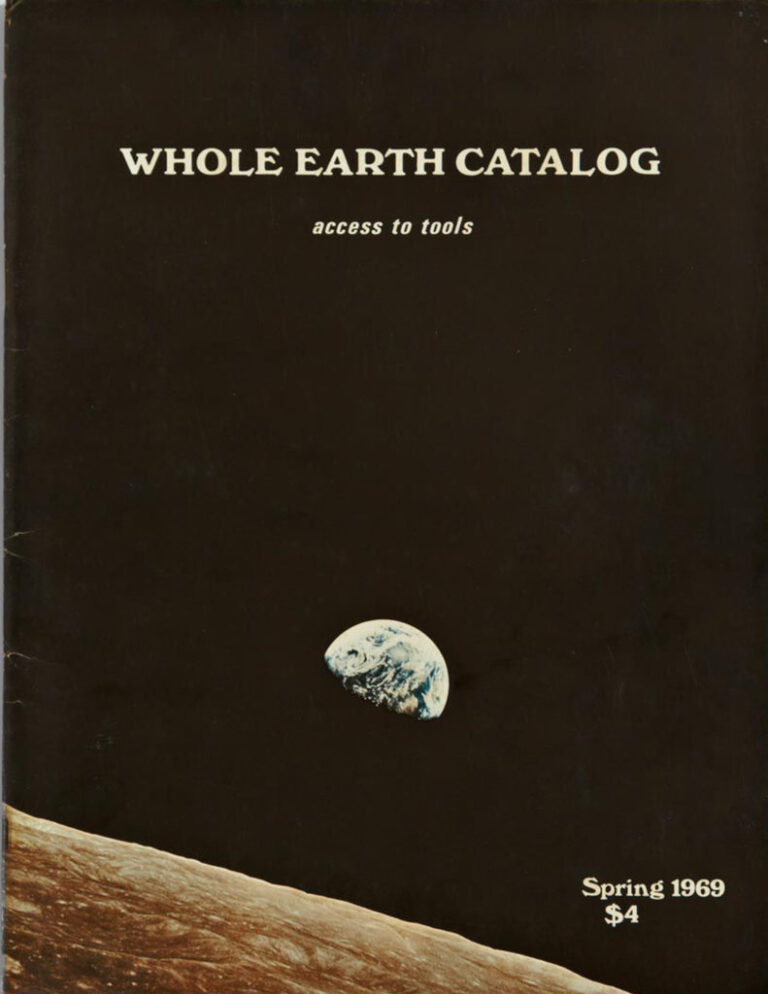

My series Whole Earth Systems relies on ideas and imagery derived from various volumes of The Whole Earth Catalog. Prior to this catalogue, which was first published by artist Stewart Brand in 1968, you may have had to seek out multiple sources, catalogues, or stores to find what you needed to live off of the land and be intellectually engaged. In this publication you could find DIY instructions, goods and tools from the most practical, (how to farm the land) to the most esoteric, (how to read auras). It followed this very utopian dream of the era, that if you could educate yourself and build your own tools you could have your own world. This was, in itself, rife with problems. For one, the detachment and disconnection from pre-existing social structures and communities.

So, after the 2016 election I decided to start The Tool Book Project as my own offer of a publication-space for tool-sharing and empowerment/consolation for artists and writers.We also organized readings, panel discussions, gallery shows and different sorts of community engaged events. The profits go to social justice and environmental justice non-profits, which I worried would lose all their funding due to the Trump administration. We have just published the third iteration now, and I can say that I am not interested in being an architect of a new community, I am interested in giving the resources that I have to make a space where we can connect, and to really engage with the communities that already exist.I personally think all art practice has a purpose and you don’t have to become a socially engaged artist if that’s not what you are trained or attuned to do. I think if you have purely formal or aesthetic concerns it has great value. So through The Tool Book Project, you can still do what you do and in the meantime part of your work can help fund all these amazing organisations that work ethically and with experience in their own communities.

[1] The Toolbook Project Instagram is now active in a ‘Social Distancing Tool Share’ experience, open to takeovers by artists and contributors to share their studio work, information about cancelled shows and lectures, tools and commiserations due to recent/current pandemic. For artists working and living in Italy interested in contributing should email toolbookproject@gmail.com or DM Sarah on The Toolbook Project IG: toolbookproject

GM: How does your publication research and the actual creation of The Tool Book Project spill into the ‘Kinship’ Project in 2019?

SGS: Kinship is the title of my current series in progress. It was developed during my most recent archival research at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County in their Radical Literature collection. I was looking at self-published feminist newsletters and magazines from the 1970’s, just before the Roe vs. Wade era, which was the famous supreme court case that legalized abortion in the US. Women were controlling all the forces of publication and writing about themselves. So, I was conducting this research and thinking about how it might be translated into textile and mixed-media works.

When I’m working in Baltimore, where I teach, or when I’m doing artist residencies in rural areas, I end up going to commercial fabric stores, often one called Joanne’s Fabrics, for studio materials. I had this ongoing experience of encountering this gender encoded place, where women who have domestic, craft-oriented and retail training work along with a few men or gender non-conforming folks. There seems to be some sense of safety in these domestic ‘making’ spaces and, despite it’s framework of commericalism, a community of sharing takes place there. During hunting season in Baltimore, and other rural and “ex-urban” places, Joanne’s often has displays of various camouflage textiles and hunter’s shirting. These stores are usually located in semi-suburban strip malls. They have a huge range of camouflages, including multi-distance camo made to disrupt the digital “eye” of a modern camera in warzones, and these are being sold in this gendered encoded setting, ideally waiting to be sewn into clothes for men to go deer-hunting.

I was also reading Donna Haraway’s Staying With The Trouble, and combined with my research into early feminist publications, this framed my thinking about the kinship between knowledge bases; who was buying these textiles, who was selling and sewing them, then who was using the sewn product and how they intersected with gender, domesticity, and again the idealized wildness of nature. The work deals with the complexities of these relationships to the land, with guns and with the interspecial relationships with the animals in question, using languages that are digital and craft-based, totemic but futuristic, celebratory but war-related.

GM: Let us end with news from your most recent feminist publication research, planned to be showcased at the start of April and now cancelled due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

SGS: I had a solo show that was going to be installed in early April at Syracuse University’s Random-Access Gallery. I was planning to show the textile work from Whole Earth Systems and my video “Finding Our Place in Space.” The gallery has two rooms, so in the smaller space I designed a reading room with excerpts from my Feminist Publication research, items from the Syracuse Library, (including a few volumes of the Whole Earth Catalog!) and a reading list “zine.” I made posters of some of the newsletter and magazine covers from my research and was making seat covers from custom fabric. The zine got a bit derailed when I realised that everything was changing, but I’m hoping to finish it soon and have it available as a kind of document of the ideas.

–

Website: https://sarahgsharp.net/home.html

Painting, Time, Oddness & Populated Space

Giulia Mangoni presents INTERVIEWS FROM LOCKDOWN: #1 A remote conversation with artist Paul Becker, most recent Abbey Fellow in Painting at the British School at Rome.

GM: If I had been able to say hello in person, I would have loved to ask you if the cigarettes in your work had any connection to Italy and Italian cinema, and I would have asked you about the time-frame that inspires you to make your paintings. They seem to me nostalgic yet very contemporary at the same time.

PB: That’s very true. They feel of a period that is difficult to define while also feeling like they are being made now. One of my tutors at the Slade used to say they looked like they were made yesterday, 150 years ago. Ha!

It’s not timelessness exactly but I am looking for them to exist in both some sort of now AND some kind of then and that happens kind of ‘instinctively on purpose’. It is quite difficult to force it, it tends to be more by intuition than design and perhaps is more related to the colour and especially the muted, crepuscular tonality. And probably me looking at a lot of paintings from certain periods, Belgian Symbolists, Spilliaert, Sickert, Decadent art and art deco/art nouveau, the Wiener Werkstätte designs of Dagobert Peche, Aubrey Beardsley. For about a year, all I looked at was Gwen John. I don’t think I ever got over that!

The cigarette/smoker theme does have something to do with that nostalgia you talked about. I could talk about smoking all day long! Like painting itself, smoking (cigarettes) now is an oddly quaint, nostalgic, belated, anachronistic activity [i].

It is also beautiful. I mean it looks beautiful and it is beautiful to paint, unlike vaping which makes everyone look like Gandalf and offers no satisfying whisps and curlicues! It is not as romantic; it contains none of the hints of exoticism even eroticism that haunt cigarette smoking. And of course, there are no real connections to death. Cigarettes are also deeply generous in terms of temporality. Cigarettes effectively gift you time.

The few minutes it takes to smoke a cigarette, as any true smoker knows, is most satisfyingly enjoyed alone. Suddenly the smoker is absolutely in the moment, set within those few minutes, enjoying being alive and engaged in an activity that is both physical and cerebral because cigarettes for me are also an embodiment of contemplation. Again, this is where the connection to painting comes in because painting for me is absolutely a thinking space. The thinking that painting produces is often more interesting than the paintings themselves. I am interested in that ‘state’ of painting which exists somewhere between daydreaming and reading and the cigarette is a very loaded cipher for that. It also gives the figures in the paintings agency, they are ‘doing’ something (though smoking, also, isn’t actually doing anything) and, because of the allusion to thinking, it also gives them a sense of autonomy. To answer the first part of your question, not films so much in this case but certainly the remarkable chapter in Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience, one of the greatest of all Italian novels, where the protagonist, Zeno talks about the problem of the last cigarette. BUT I did see this film about the philosopher Hannah Arendt which had an impact on my thinking. It wasn’t a particularly great film, but they needed to show her thinking because it was kind of her job and the subject of the film, and they did that merely by having her in a room, on a couch, on her own, looking off into the distance and very slowly smoking a cigarette.

So, again, the cigarette is a manifestation of pensiveness, of thought and most importantly of all, of reverie, daydreaming.

[i] My friend Francesco told me about this oddly moving series of filmic portraits that the French director Alain Cavalier made in the 1980’s, about older women who were still engaged, mostly in Paris, in trades or activities that were about to disappear (because of mechanisation or digitalisation etc.). They all worked with their hands, on tasks like corset making, mattress stuffing, hand stitching books and jobs like that and they were all the last people who would ever be engaged in them that way, jobs that had continued for generations. It reminded me of something Walter Benjamin said about finding new beauty in that which was vanishing and, of course, it reminded me of how odd and outmoded it often feels to be a painter.

GM: The sinister, perverse nature of some of these works’ seeps through defenses, superficially pleasing with their non-threatening flatness, their pastel tones and playful subject matter. Yet something disrupts the narrative, maybe it’s a gaze outside of the picture plane, or uncomfortably long feet, limbs holding strange objects or faces caught in unpaintable moments. I wonder if you work until an oddness is reached, if you know from the beginning what this oddness must be and if the original subject matter is transformed through the act of painting so as to reveal its ‘strange self’.

PB: I partially answered this already in terms of agency and autonomy. It is important that the figures have a life, not just the women in the paintings but all the figures. I think, again they are emblematic of something about painting itself. I have very unconventional beliefs about painting that border on the esoteric. I believe that an autonomous vessel containing both emotion (feeling) and intellect (thinking) can make a perverse claim to a unique kind of sentience. I think certain paintings, really do have a form of life, obviously not as we understand life, but they do have a singular existence, a state of being involving time and space and dream. When I was teaching painting I was always talking about letting paintings breathe, not killing them by overpainting…

To respond to you in another way I am always battling with the problems of being a figurative painter and the problem of the figure itself, especially if, like me, one is not using any form of reference material: no photographs, no drawings, nothing. Because I am not interested in the figure looking ‘real’ (god forbid) or like a photograph because I am using my imagination only and while I like the reverse constraints of that, I also don’t want the figure to look whimsical or twee so it can be dismissed or neutered as something childlike. I want it to be mine, I want it to look like something arriving barefoot in the world, for the first time. This is what excites me about painting in oils, its capacity to facilitate exactly that. So, to do that I make the figure a bit more mannered, a bit more like it has its own physical rules.

GM: Cats, foxes and dogs populate your work… so do backs of heads, clothes that seem animated of their own accord and hair that sometimes overwhelms the wearer. A friendly animal seems to almost strangle a neck, yet there is never a feeling of urgency or alarm. The population of intimate space seems to allow you to juggle certain unnamable concoctions of emotion at the same time, creating work that leaves one wanting sequels. What is the space you work in? Where does it come from, where does it go?

PB: This is a very generous question. I really appreciate it because I really feel it comes from behind a set of eyes, from someone who has looked very carefully at the work, so thanks! That said, I feel I am unable to do it full justice because I’m not convinced I have a cogent answer to this. Yes, you are right, certain motifs reoccur though I am really wary of repetition, it does creep in. I mentioned this thing earlier about wanting to put things in the world for the first time and so everything I don’t scrape off or paint over has to have surprised me in some way, even if I am not reinventing the wheel. The space isn’t exactly theatrical, at least in my understanding of that term but it is close, everything happens in a space that is meant to have a close physical relationship to the viewer. When I was a student I read one of the School of London painters had said that paintings should be like flags, you should be able to see them from across the room and though I don’t really agree with that at all, I do think in my paintings clarity is important, in that the viewer should be able to see exactly what is happening while at the same time what is going on is completely ambiguous, the two things are quite different. And I think the ambiguity, the mystery is fundamental. In effect, if they are ‘about’ anything, it is probably that. They are not meant to be ‘read’ or explicated. My old colleague from Newcastle, Giles Bailey always used to say that art is a really bad tool for delivering clear, readable meaning and a very good tool for offering equivocation, ambiguity. I don’t think my job as an artist is to know. I’m not sure what it is but it is certainly not that. Perhaps that sounds like a cop out? But, I mean here we are, careering though an endless, dark void, with no idea about anything apart from the fact that one day it will all stop and to me it’s heartening to know a vocation still exists that is able to represent something of all that instead of pretending it has all the answers. So, not only did I not have an answer to this question, it turns out that is actually my job! Hahaha!

–

IG: mrpaulbecker

Becker’s most recent paintings would have been exhibited at the BSR’s Marzo Mostra, now cancelled due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

https://britishschoolatrome.wordpress.com

Recent Writings:

2020 Co-Editor: A Table Made Again For The First Time: On Kate Briggs’ ‘This Little Art’ (with Kate Briggs, Daniela Cascella, Sophie Collins, Renee Gladman, Nadia Hebson & Alejandro Zambra, Published by Juan de la Cosa, Mexico.

2018 Legsicon for Laure Prouvost (with John Latham, Elizabeth Price, Natasha Soobramanien, Agnès Varda, Emily Wardill, Marina Warner & Lawrence Weiner) Published by Bookworks, London & M_HKA, Antwerp, Belgium

The Kink in the Arc, Collective novel

Choreography, ARCADE, London & Choreography/Coreografia Juan de la Cosa, Mexico

the garden – part three

IMPORTANT: use headphones if possible.

The Garden is a series of videos exploring a semi-abandoned courtyard between three blocks of flats in Monteverde quarter, Roma.

the garden – part two

IMPORTANT: use headphones if possible.

The Garden is a series of videos exploring a semi-abandoned courtyard between three blocks of flats in Monteverde quarter, Roma.

the garden – part one

IMPORTANT: use headphones if possible.

The Garden is a series of videos exploring a semi-abandoned courtyard between three blocks of flats in Monteverde quarter, Roma.

Look at the change, Look at the future

Le forme verbali del condizionale, come quelle del futuro, sono espressione di modalità: questo vuol dire che indicano, ognuna a modo suo, una certa insicurezza.

Il condizionale è un modo verbale abbastanza comune nelle lingue europee. Viene usato soprattutto per indicare un evento o situazione che ha luogo solo se è soddisfatta una determinata condizione. Si adatta, in diversi casi, ad esprimere il concetto di futuro nel passato.

Numeri di emergenza in sotto-impressione. Preparare un viaggio oltre un metro e mezzo. Tutte le cose che stavamo dando per scontato e che non lo erano.

Si potrebbe cercare di immaginare cosa sarebbe diventata questa città se…

Per cominciare non sarebbe servita la divisione dei giorni della settimana, ma al massimo quella tra il giorno e la notte, ne sarebbe credibile il concetto di Vacanza.

Sapremmo che non esistono spazi superflui o non inutilizzabili, ogni cosa avrebbe alcune dimensioni prestabilite, fitterebbe.

Naturalmente conosceremmo la velocità e l’immediatezza come adesso apprezziamo il viaggio e il movimento, quello spazio temporale e fisico tra un punto di partenza e uno di arrivo.

Jack Kerouac sarebbe semplicemente stato un affascinante alcolizzato che viveva con sua madre.

Preferiremmo i workout che prevedono braccia e addominali; ci rivolgeremmo sempre agli altri dandoci del Tu :

Guarda, Connetti, Cerca, Apri, Chiudi, Salva, Esporta, Condividi, Linka, Chatta, Imposta, Copia, Incolla, Taglia, Leggi, Rispondi, Allega, Digita, Approva, Acconsenti, Registra, Inserisci, Apri, Mostra, Nascondi, Elimina, Visualizza, Salta, Annulla, Ripeti, Seleziona tutto, Cancella, Trova, Avvia, Riduci, Limita, Imposta, Disponi, Dividi, Attiva, Personalizza, Torna, Interrompi, Ricarica.

Andremmo definitivamente a perdere i sensi che non siano l’udito e la vista – Mi vedete? Mi sentite? – dimenticandoci di odori, consistenze e temperature: del profumo umido della pioggia, della temperatura del sole di aprile ma, soprattutto, della ruvidezza delle superfici.

10 ore – il rumore della pioggia e dei tuoni

Saremmo a riparo, avremmo molte meno paure perché non esisterebbe il buio o il confronto diretto.

Staremmo attenti ad avere le lenti adatte, nell’impossibilità di riposare gli occhi – To wash all of these fears away; Thought’s too loud, no words to say; Rest your eyes, you’ll be okay – .

Ci piacerebbe piuttosto che l’ozio, l’intenzionalità, anche minima, la sensazione sommessa di “fare cose” e di essere update.

Aiutaci a respirare tranquilli, dicci chi chiamare in caso di necessità, in caso di freddo. Comunicaci quali sono i luoghi in cui sentirci al sicuro.

Accetteremmo finalmente Il ritardo del discorso sul pensiero.

Spontaneamente avremmo meno scarpe, non esisterebbero più pagamenti in nero, né tutte le cose fatte in segreto o di nascosto. Ci insegnerebbero, fin da bambini che ogni azione, ogni dato è da proteggere.

Take a break . Go offline

Try to see the boundaries and the limits

Who is born with Microsoft (1975) today is 45; Who is born with the web (1991) today is 29; with Google (1997) is 23; with Skype (2003) is 17 with Facebook (2004) is 16 years old.

Try to distinguish yourself from what’s around you

Try to distinguish yourself from what’s around you

17/03/2020 (9th day of quarantine)

While you study suspiciously these spaces that are supposed to be your home, try to distinguish yourself from what’s around you. What’s me? what’s not?

“Try to love the questions themselves as closed rooms” [1]

ps. Several of the people I know, for the first time yesterday, told me they were not so well

[1] Rilke Rainer Maria, Letters to a Young Poet

If the space seems to be either tamer or more inoffensive than time

Perec Georges, Species of Spaces and_Other Pieces

Rebecca Moccia

Viale delle Milizie, 94

5th floor

Right door

Roma Prati

Italy

Europe

The world

The universe

We’re proud to say that CASTRO Fellow Giulia Mangoni has been selected to participate to this show while at CASTRO.

“WORKS ON PAPER” CURATED BY SOFIA VOLLMER MADURO

“Works on Paper” is an art show exploring art on paper, highlighting differences in technique, style, and presentation. In addition to our wonderfully talented Resident Studio Artists (Clemente, Stephen Johnson, Ellen Liman, Mary Ourisman, Ezra Hubbard, Weatherly Stroh, Cloe Gibson, Charles Bane III), we have selected guest artists to show their incredible works on paper, including: Bruce Helander, Adam Dolle, Maureen Fulgenzi, Camilla Webster, StrosbergMandel, Pamela Acheson Myers, Ann Friedlander, Paul Gervais, Jacqueline Benyes, Nuné Asatryan, Elle Schorr, Annette Colon, Jason Mena, Cara Arlette, Giulia Mangoni, Dan Leahy, Alexander Shundi, Alyssa Shuey, Erica Elliott, Sammi McLean, Leora Armstrong, Ingrid Schindall, Nita Miller, and Fransisco Prettell.

Opening Date: March 12, 2020 – Closing Date: April 4, 2020

Time: 5:30pm – 8:30pm

Location: Studio 1608

1608 South Dixie Hwy

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

We’re proud to say that CASTRO Fellow Stefania Carlotti has been selected to participate to this show while at CASTRO.

Usefulless

Curated by Clément Delépine e Mélanie Matranga

Artists:

From November the 8th to November the 15th

WHAT IS A CRIT?

CRITS are an American born format which subsequently landed in Europe, in the United Kingdom. They have been one of the cornerstones of education for decades in schools such as Goldsmiths, and are progressively establishing themselves in many institutes and academies of other European countries.

A CRIT is a meeting in which artists present their work, “offering it” to a collective criticism. The CRIT public has the mandate to observe and understand the work that is presented.

The artist briefly introduces the work / project, and then the public may intervene, offering their point of view on the work, making comments or questions and triggering a dialogue with the artist.

The core of CRIT is the exchange between artist and public: CRITS are a collective ritual, and can become opportunities to negotiate shared values and meanings.

CRITS are based on the idea that group discussions can enhance the practice of the artist, bringing a degree of objectivity in the highly subjective dynamic of the private creative process. Making art is often a solitary search, and it can sometimes be difficult for an artist to evaluate if his work is on the right track, if the way he is progressing is approaching his goals. A CRIT is an opportunity for the artist to better understand his artistic practice, his work and himself.

John Baldessari, who has led CRIT classes since the 1970s, constantly reminds his students that “Art comes out of failure. You have to try things out. You cannot sit around, saying ‘I will do nothing until I do a masterpiece’. ” For Baldessari CRITS are fundamental as a moment of “demythizing” the figure of the artist and the idea of a work of art.

CASTRO 2018/19 – Activities’ Photo Album

We’re proud to say that CASTRO Fellows Alberta Romano and Vincenzo Di Marino are curating this project in Ansedonia.

VOI RUBATE DEL TEMPO ALLA FRETTA, A NOI IL MARE CI IMPONE LENTEZZA

a cura di Enzo Di Marino e Alberta Romano

un progetto di CASTRO

Villa Di Lorenzo, Ansedonia

Artisti in mostra:

Apparatus 22 / Adam Cruces / Caterina De Nicola / Débora Delmar / Gaia Di Lorenzo / Joana Escoval / Marco Giordano / Allison Grimaldi Donahue / Joshua Hopping / Dana Lok / Davide Mancini Zanchi / Ana Manso / Catherine Personage / Marco Pio Mucci / Jacopo Rinaldi / André Romao / Giulio Scalisi / Luca Staccioli / Jennifer Taylor / Hannah Tilson / Ilaria Vinci

In occasione del secondo capitolo di HYPERMAREMMA, organizzato da Giorgio Galotti e Carlo Pratis, CASTRO Project presenta la mostra collettiva Voi rubate del tempo alla fretta, a noi il mare ci impone lentezza a cura di Enzo Di Marino e Alberta Romano negli spazi di Villa Di Lorenzo.

L’estate è iniziata, il caldo comincia a diventare sempre più logorante, le forze vanno scemando e cresce l’esigenza di ridurre i ritmi lavorativi verso una presunta improduttività vacanziera. Nel contesto di un festival estivo la mostra si propone come un vero e proprio summer show che, con l’estate alle porte, abbracci e inviti chi la visita a riscoprire le potenzialità e la bellezza di un puro ozio vacanziero. La mostra ha come obiettivo quello di restare in linea con questi principi e con l’affascinante ambiente che la ospita: un imponente architettura brutalista, minata e contaminata dalla natura. La casa sorge su uno scoglio e affaccia direttamente sul mare, colate di cemento grezzo vengono intervallate da immense vetrate e giardini segreti.

Voi rubate del tempo alla fretta, a noi il mare ci impone lentezza, vuole essere un invito a rallentare, a “prendersela con calma”, mettendo insieme artisti che hanno avuto tempo di conoscersi durante il periodo di CASTRO studio program a Roma e artisti che, con la loro, a volte, semplice ironia, tentano di stemperare una rigidità di convezione, un intellettualismo a tratti superficiale, che ostenta sempre una rigorosa serietà. Non si parla di improduttività come una forma di resistenza all’invasione e al controllo del tempo lavorativo nella vita di un individuo, non si parla di biopolitica, questa mostra vuole essere un semplice freno, “un’imposizione di lentezza” finalizzata a una più accurata e onesta osservazione di ciò che ci circonda. Per essere in linea con quest’idea, i due curatori hanno deciso di non intervenire con un contributo testuale, ma con una playlist su Spotify che raccoglierà quelle che, sulla base di un personalissimo gusto, possono essere considerate canzoni che trasmettano agli spettatori una sensazione di rilassatezza, un invito a godersi la vita, un tempo di pausa su cui si riflette semplicemente la vista del mare.

Un ringraziamento speciale a CASTROprojects, Hypermaremma, ACAPPELLA, Galleria Umberto Di Marino, Gallleriapiù, Clima, Giorgio Galotti, Frutta, Operativa Arte Contemporanea, 650mAh.

We’re proud to say that CASTRO Fellow Caterina De Nicola has been selected to participate to this show while at CASTRO.

Le ciel, l’eau, les dauphins, la vierge, les flics, le sang des nobles, l’ONU, l’Europe, les casques bleus, Facebook, Twitter

Exposition du 8.02 au 17.03

Mélanie Akeret, Marilou Bal, Trudy Benson, Deborah Bosshart, Vittorio Brodmann, Ralph Bürgin, Guillaume Dénervaud, Anna Diehl, Natacha Donzé, Othmar Farré, Marie Gyger, Catherine Heeb, Séverine Heizmann, Lauren Huret, Ken Kagami, Jan Kiefer, Real Madrid, Laure Marville, Thomas Moor, Flora Mottini, Kaspar Müller, Markus Augustinus Müller, Caterina de Nicola, Jean Otth, Max Ruf, Arnaud Sancosme, Liem Truong, Andrew Norman Wilson

We’re proud to say that CASTRO Fellow Jennifer Taylor has been selected to participate to this workshop while at CASTRO.

Testing Ground Master Class is a week-long intensive for emerging artists developed in collaboration with artist Doug Fishbone at the Zabludowicz Collection.

Now in its seventh year, Master Class offers a unique and free opportunity for eight emerging artists selected through a national Open Call. Over the course of a week, the participants work closely with leading international artists and key arts professionals to discuss and develop their individual practices through a series of lectures, tutorials, workshops, gallery visits and seminars.

The week is structured around four public lectures and closed teaching days from guest artists. The guest artists this year are Janice Kerbel, Haroon Mirza, Keith Piper and Amie Siegel. Previous guest artists include Jake Chapman, Michael Dean, Richard Wentworth, Monster Chetwynd, Marcus Coates, Omer Fast, Joseph Kosuth, Linder, Heather Phillipson, Elizabeth Price, and Mark Titchner, among others.

The emerging artists participating in this year’s initiative are: Catalina Barroso-Luque(Scotland), Alexandra Brunt (Northern Ireland), Steve Burden (South West), Claire Davies(Midlands), Jure Kastelic (London), Angel Rose (South East), Jennifer Taylor (Wales),Joshua Ward (North). Past participants have gone on to have exhibitions at Hannah Barry Gallery (Lindsey Mendick, Master Class 2015), Matt’s Gallery (Bronwen Buckeridge, Master Class 2014), Jerwood Gallery (Chris Alton, Master Class 2017, Joe Fletcher Orr, Master Class 2016, Simeon Barclay and Lindsey Mendick, both Master Class 2015), Liverpool Biennial 2018 (Holly Hendry, Master Class 2016), Vitrine Gallery (Sam Blackwood, Master Class 2018), and Tate Britain (Simeon Barclay, Master Class 2015).